The Galapagos Islands are famous for plant and animal life which has been there for thousands of years before human beings appeared on the islands. As the population of the Islands grow, it is important to monitor the impact of the human population on the environment.

Where do people live in Galapagos and how is the population growing?

Only four of the archipelago’s thirteen major islands have human populations: Santa Cruz, San Cristobal, Isabela and Floreana. In total, only three percent (or 300km2) of the Islands have human settlements, (the remaining 97% of the Galapagos Islands is maintained as national park). Therefore, as the population of the Islands grows, this space gets more and more crowded. The permanent resident population of the Islands is currently growing by around 6.4% a year, compared to population growth of 2.1% in mainland Ecuador. Both natural population growth and migration to the Islands are having an impact on this growth as the Islands become a more attractive place to work and live.

Land Zoning

“The ultimate purpose of zoning is to avoid or minimize the negative effect of human impact. Galapagos ecosystems are subjected to and allow for a rational use of goods and services these ecosystems offer to society.”- Galapagos National Park

Isolation is the key to the special nature of the Galapagos archipelago. Because human colonisation in Galapagos did not occur until relatively recently compared to the majority of the rest of the world, the unique ecosystems have been preserved and species have survived. However, population increase and urban expansion means that land zoning of areas for human use and rules for the use of the zones has become necessary.

Prior to 1959, protected areas and unprotected areas were considered independently and the interconnectedness of the zones was not taken into account. There was no real difference in the management of the human and natural space. When the Galapagos National Park was defined in 1959, 97% of the islands around populated areas were declared protected natural areas. The remaining 3% of the land is used by Galapagos communities both rural and urban. The new zoning model recognises that hazards such as invasive species and pollution come from populated areas and that the populated areas depend on the unique ecosystems and their conservation, so demonstrating the inter-connectedness of the zones.

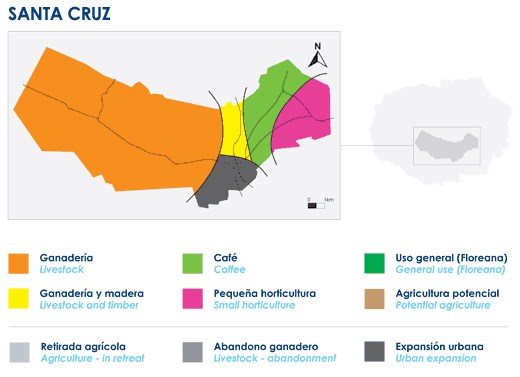

A digram showing land use in the rural part of Santa Cruz © Galapagos National Park

Rural areas are in the upper parts of the inhabited Islands and are privately owned. They are wetlands which allowed the formation of soil suitable for agriculture. This importance of agriculture has declined and the land has gone out of cultivation. This has led to an increase in the invasive plant species such as guava, blackberry and passion fruit, that were introduced when the land was cultivated. The responsibility of recovering these areas, preventing further invasions and removing the invasive species lies with the owners, local government and government. A pilot plan on Santa Cruz Island in 2009 used chemical and physical controls such as cutting back plants, foliage spraying and fumigation.

The urban areas around ports are where most human activities take place, such as the arrival of cargo and people from other islands and the mainland. Human activity causes the greatest changes to the environment through construction of buildings and roads, pollution and introduced species. It is therefore very important to have clear land use policies and planning.

Urbanisation in Galapagos © Galapagos Conservation Trust

Surrounding rural and urban human spaces on each populated island is an area defined as low impact. These are areas which have much of the original ecosystem still intact but have been altered to some extent by human activities. The establishment of Special Public Use Sites is allowed so that some timber can be extracted and non-recyclable solid waste can be disposed of.

The Marine environment is also subjected to zoning with a Marine Reserve and coastal areas with different uses in specific locations for fishing, research, conservation and education. There are sub-zones for special management and recovery, in which human activity is particularly relevant.