Between the late 1500s and 1700s many pirates occupied the Islands. The Spanish Empire had conquered large parts of Latin America, also know as the New World. Occupation of the New World was providing Spain with a vast amount of gold, which was sent back to Spain on ships. The rest of Europe, mainly France and Britain, were getting nervous about Spain’s increasing wealth and power. These diplomatic tensions led to a lot piracy and privateering.

The golden age of piracy

Pirates began to use the Galapagos Islands as a place of refuge to hide from pursuers. The Islands were perfectly placed in the Pacific Ocean, making them a great strategic position from which to raid the mainland.

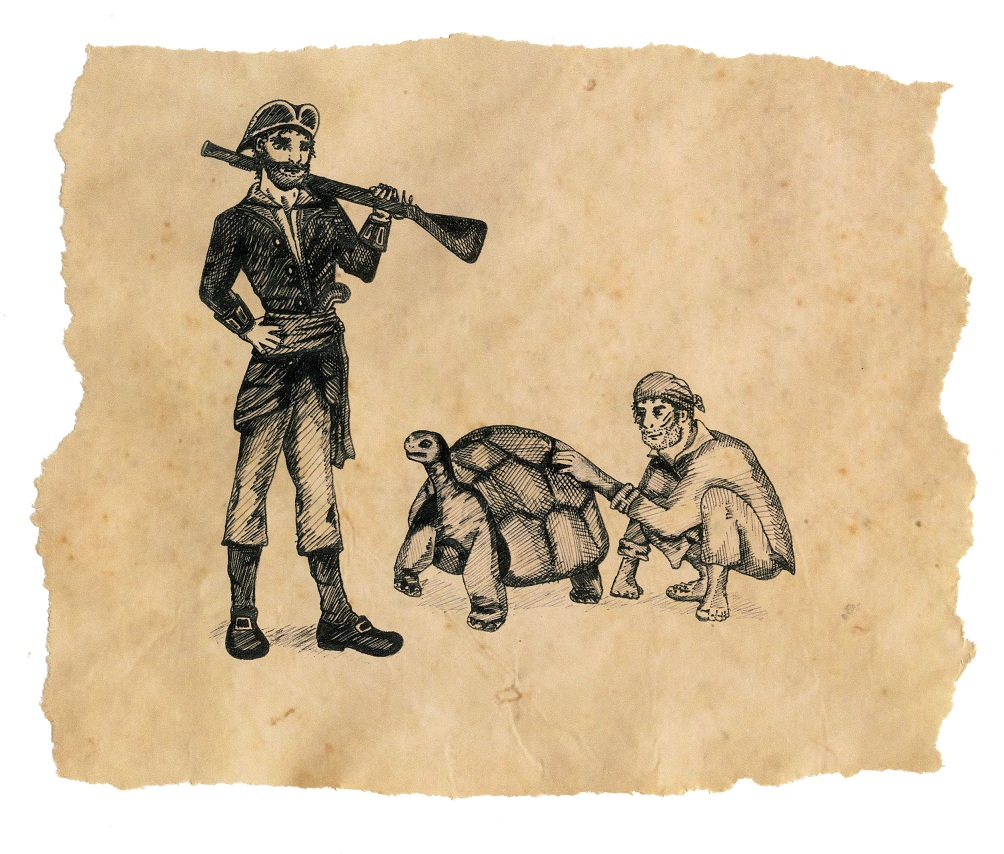

The Islands were close enough to allow for raiding, but remote enough to make escape possible. The Islands also provided much needed supplies of fresh meat for the pirates, but the water was scarce, so they never stayed on the Islands too long.

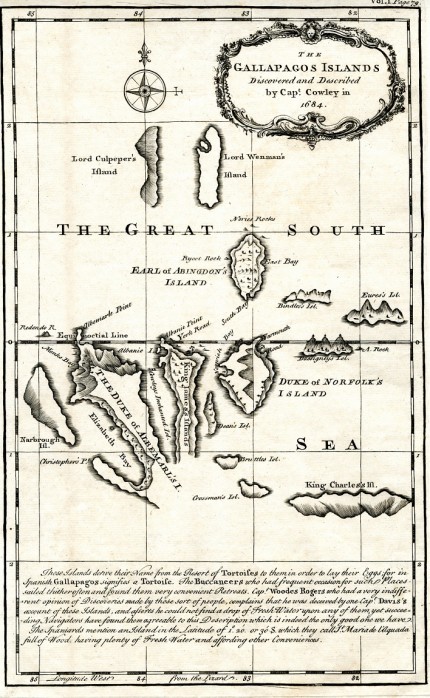

In 1684 the ship ‘Bachelor’s Delight’ had to take refuge on Santiago after Captain John Cook fell ill. They landed on Buccaneers Cove and a crew member (Ambrose Cowley) made a navigation chart of the Galapagos Island.

In 1697 Englishman William Dampier published his book ‘A New Voyage Round the World’ showing the Galapagos from a naturalist perspective. In 1708, Dampier returned to the Islands.

On the way, he rescued Alexander Selkirk from the Juan Fernandez Islands near Chile. It is thought that Selkirk inspired the story of Robinson Crusoe.

Rise of the whalers

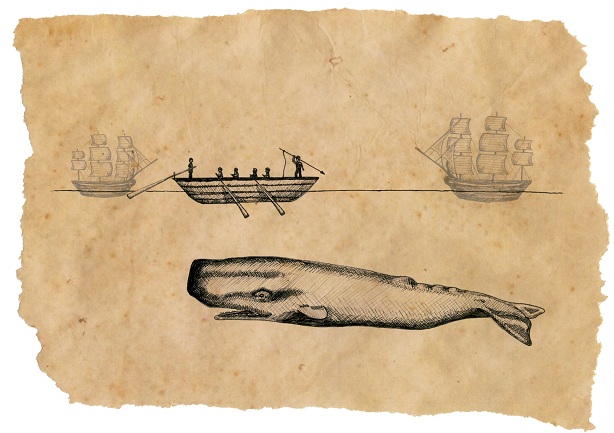

Eventually, piracy started to decrease and a business where more money could be made started to gain popularity. This business was whaling. During the 19th century, Spanish power in Latin America was declining and countries began to trade independently with England.

Pirates discover the giant tortoises © Katie Meads

There was a demand for whale oil and not for Spanish gold. English and American whaling vessels began to explore the Pacific Ocean after the whale population in the Atlantic Ocean declined.

Whalers on the hunt © Katie Meads

In 1793 the English Captain James Colnett was sent to investigate the Islands’ potential for whaling. The map that Colnett’s investigations produced is attributed with alerting whalers to the area and increasing whaling in the Galapagos Islands for over a century.

In 1813 the US Frigate Essex, headed by Captain David Porter, fought and captured a number of British whaling ships in Galapagos. He also released four goats onto the Island of Santiago – the descendants of these goats quickly grew to outnumber indigenous species on the islands and are now labelled an invasive species.

The Galapagos Islands were one of the main whaling sites until a whaling base was established in Japan in 1819. This meant that there were huge losses to the whale population in the area, and fur seals were close to extinction. The number of tortoises also drastically declined around this time period. According to whaler’s logs, between 1811 and 1844, around 15,000 tortoises were removed for food.

Previous: Exploring Galapagos – Discovery of Galapagos