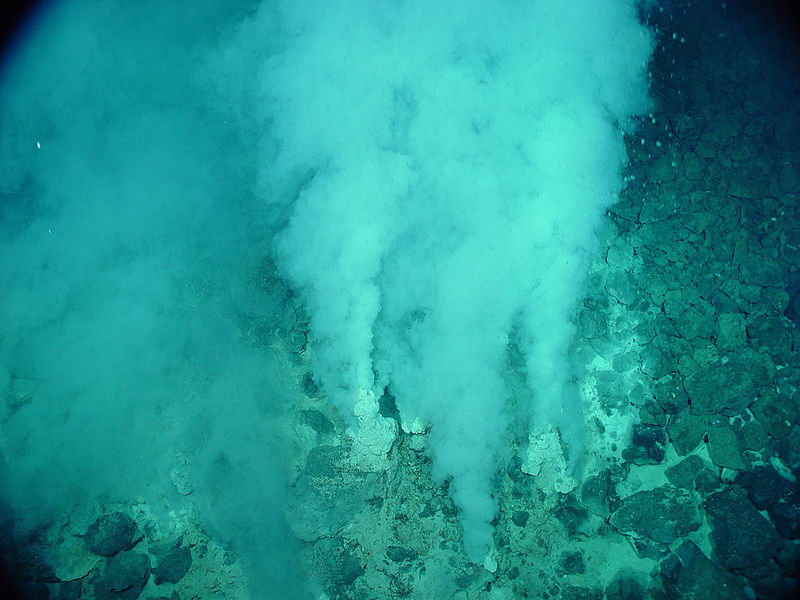

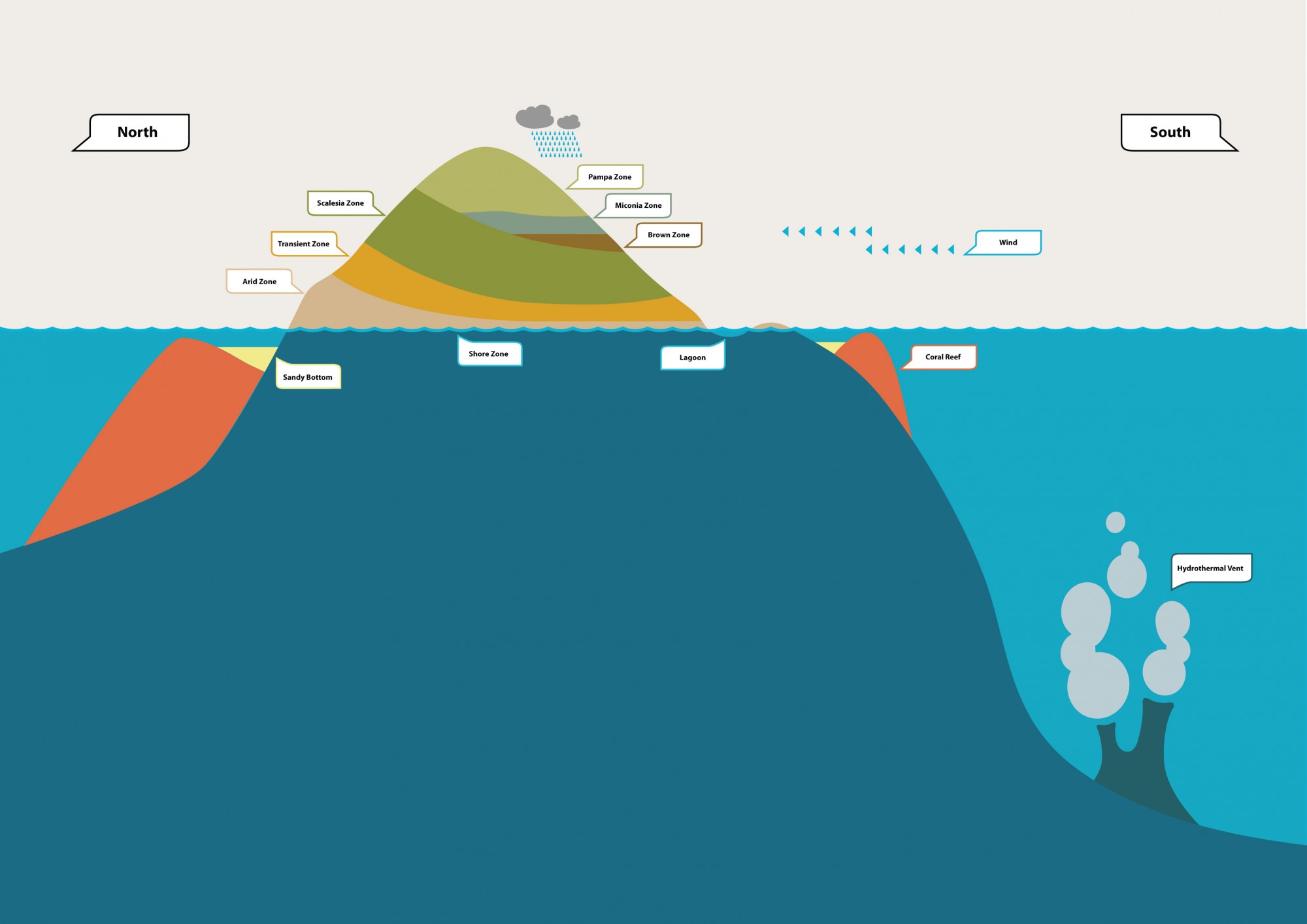

A new island is formed when volcanic lava erupts out of the sea bed, over 1,600m below sea level. On contact with cool sea water, the lava solidifies into volcanic rock at the bottom of the ocean. As the eruptions continue, rocks build up until they rise above sea level to create a new island.

Colonising Galapagos

Galapagos colonisation: starting life on bare rock

Newly formed islands are devoid of life. The first things to colonise the islands are small and basic organisms (e.g. lichen, algae and mosses), able to cope with the harsh environment. Washed up on the shoreline or blown by the wind from the South American mainland, these pioneer species are the first forms of life on the bare rock.

Pioneer species are producers, so are able to create their own food from only sunlight, water and air (photosynthesis). Over time, they break down the rock to create soil and help to provide a more hospitable environment. This process allows more complex, less resilient plants to grow on the island.

Mosses and lichens are often the first colonisers of bare rock © Galapagos Conservation Trust

Establishing an ecosystem

An ecosystem is the community of living things found in an area and also the non-living things that make up the environment such as rock, water and air. All of these elements interact with each other in a system… an ecosystem!

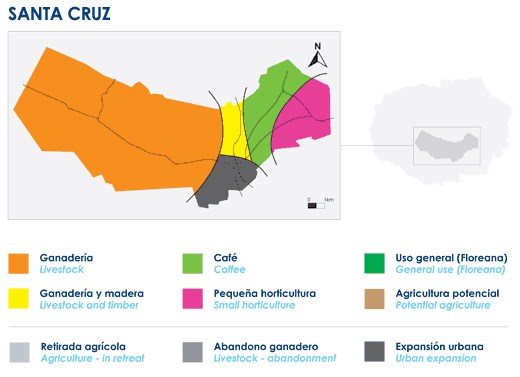

As the amount of life on the island increases, the environment continues to change. A deeper, more nutrient-rich soil can support the growth of species that would previously have struggled to live on the island. With time, this allows larger plants and trees to grow. The transformation of bare rock into rich habitats is known as lithosere succession.

Once sufficient vegetation is growing on the island, animals are able to survive in this new environment. Small animals such as insects will often be the first to arrive as they are primary consumers and only need plants to survive. The presence of insects in turn helps more plants to colonise the island due to their important role in pollination.

As ecosystems develop, the islands will be able to support secondary, tertiary and quaternary consumers, such as iguanas, birds and sea lions.

A long way to travel

Remember, animals have to travel almost 1,000 kilometres from the South American mainland to reach the Galapagos Islands. This is just over the length of the British Isles from north to south.

There are two key methods of transport – by air or by sea. Since many plant seeds cannot survive submersion in saltwater, they would not have been able to colonise the volcanic islands. Only the hardiest seeds, that can survive in saltwater for long periods of time, would have been able to travel to Galapagos. Spores would be able to reach the island by travelling in the air, as they are much smaller and lighter. Seeds and spores may also arrive via animals for example, on the feather of a bird or via its dung if eaten on the mainland.

Sea birds that are strong flyers may be able to cross the ocean to the island during their long migrations but weaker, smaller land birds and insects rely on just the right wind conditions to help them along on their journey.

Strong swimming marine life such as tuna and sharks may swim to the island but smaller species of fish and seabed dwelling animals such as crabs depend on ocean currents to reach the new island. The Galapagos penguin is the most northerly penguin species in the world.

The cold Humboldt Current that travels up the western coast of South America from Antarctica, is likely to be the route that the ancestors of the Galapagos penguin originally took when they first colonised the Galapagos Islands.

The Galapagos penguin is the only penguin to be found on the equator from left to right – ©Bart Goedendorp, ©Antje Steinfurth, and ©Jonathan Green

Some animals, such as lizards, probably floated from the South American mainland on rafts of vegetation. Young giant tortoises may have also arrived this way but it is possible that adult giant tortoises could have floated that distance due to their ability to survive for long periods without food or fresh water.

Not all colonisers make it however. The isolation of Galapagos and inhospitable nature of a new volcanic island limits the number of species that can populate. For example, mainland Ecuador has a wide variety of plant life – more than 20,000 species – whilst Galapagos has around 1,500 species. The 1,000 km of saltwater between Ecuador and the Islands acts as a barrier to the migration of many plant and animal species.

Often colonisation depends on the right environmental conditions and a species can only succeed if it can reproduce. Physical capabilities and a degree of luck have therefore determined the wildlife that is now established in Galapagos.